The Fair & Equitable Dialogues Series highlights research, evidence and practices from a diverse array of actors around the world to address the complex themes surrounding unequal power dynamics, decolonization and localization in international humanitarian, peacebuilding, and development work.

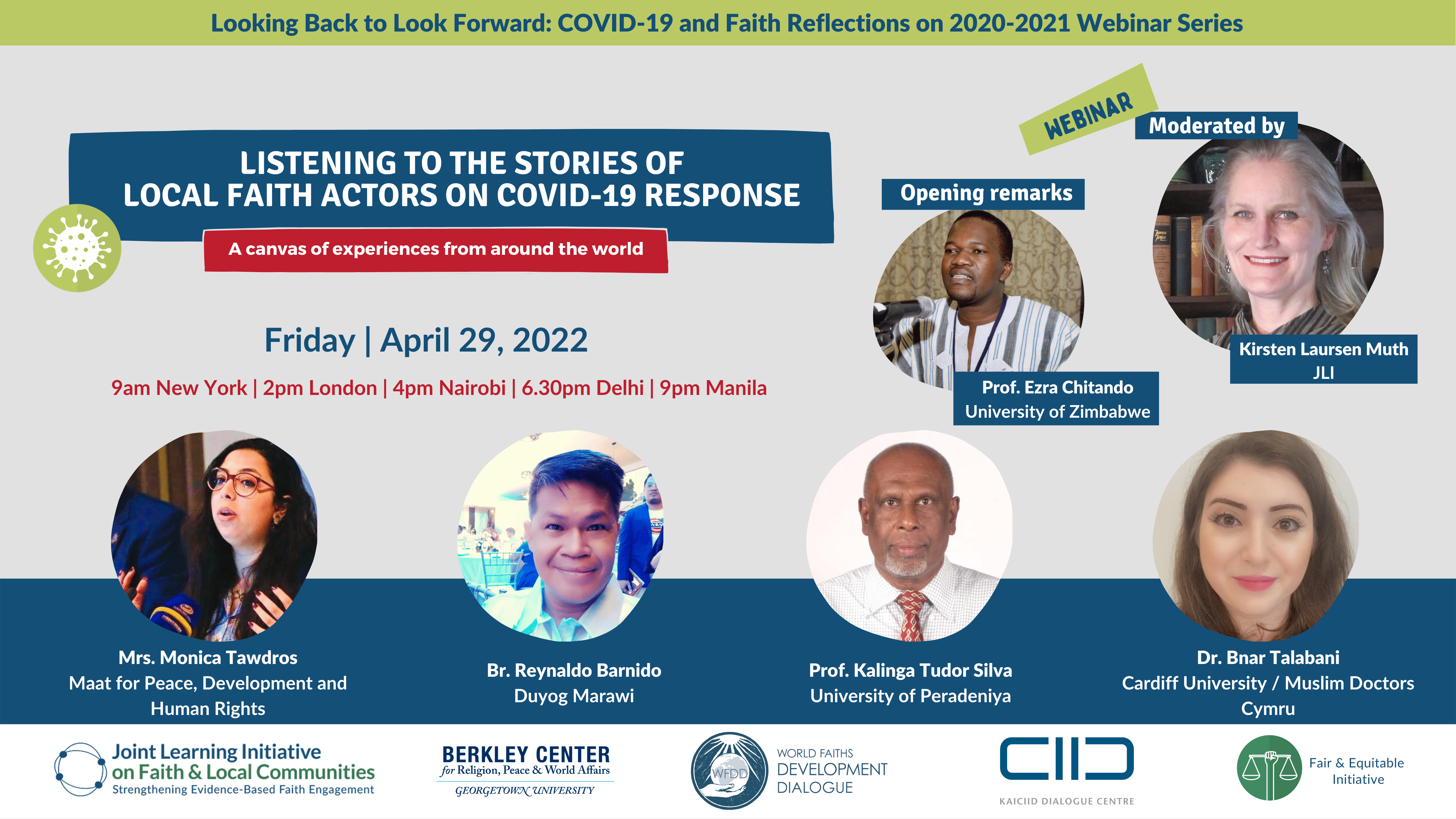

The series held its third public webinar, “Listening to the Stories of Local Faith Actors on COVID-19 Response,” on April 29, 2022, where a panel of local faith actors, academics, and activists came together to discuss their own experiences, challenges, and lessons learnt from faith-engagement during the pandemic.

Panelists drew on a diverse range of contexts including Sri Lanka, the Philippines,Egypt, and Zimbabwe, among others, to discuss challenges and successes around issues of mental health, misinformation, gender, and peacebuilding during the pandemic. The webinar concluded with each of the panelists sharing lessons learnt for the future.

Professor Ezra Chitando of the University of Zimbabwe opened the discussion with a powerful metaphor comparing people during the pandemic to a chameleon. “Just as the eyes of a chameleon have the ability to look in multiple directions at once, so people during the pandemic looked to the past and the future at the same time,” Professor Ezra metaphorically explained.

He also noted that faith actors were first line responders, disseminating material help such as food and life packs, and immaterial help such as information and psychosocial support. His powerful example of South African churches that came together to condemn government corruption during the pandemic response is emblematic of the importance of faith actors. He concluded by pointing, first, to the important role of women in faith communities, and second, to the ways faith communities can be equally as problematic as they are essential in the pandemic response.

“Even as we [in the faith communities] have achieved a lot, there were some problematic dimensions that needed to be and still need to be addressed.” – Professor Ezra Chitando

I. Key Themes

Faith actors’ responses to diverse community beliefs and behaviors during the pandemic

The four panelists began their discussion addressing the question of the beliefs of local faith actors towards the pandemic. Much of the conversation highlighted the common challenges of misinformation, technology, the relationship between faith and science, the relationship between faith and the state, social stigma, and community. However, the panelists also shared various success stories of navigating these challenges.

Challenges:

Misinformation:

The difficulty of dealing with misinformation was a common struggle faced by all the panelists, particularly around vaccines. Panelists pointed to vaccine hesitancy originating from a deep history of distrust between the people and authorities, such as the state. In addition, faith actors were concerned that vaccines would violate their religious practice. This hesitancy was compounded by the overall confusion and isolation characterizing the initial phases of the pandemic.

Technology

For many of the panelists, technology played an important role in the pandemic. In particular, panelists noted challenges arising from the way social media facilitated the spread of misinformation. However, technology also provided solutions to some of the same problems it creates.

The relationship between Faith and the State

Panelists spoke freely about the challenges they faced in conversation with their respective governments. Governments were critiqued for inconsistent messaging and policy, which facilitated misinformation and distrust in authority. Panelists also noted that governments did not include faith actors in the decision-making process despite their importance in humanitarian responses, instead putting up sometimes literal roadblocks between faith community leaders and their constituents.

The relationship between Faith and Science

As an extension to the relationship between faith and the state, some panelists noted the inherent bias that pitted religion against science, leading decision-makers to deliberately exclude the perspectives of local faith leaders. Policies may have emphasized “universal best practices” rather than listening to local faith leaders who were more sensitive to community needs. This is part of a larger systemic faith illiteracy that has been known to prioritize material needs over spiritual needs, or act against the interests of some faith communities in the name of public health.

Social Stigma

Multiple panelists acknowledged the ways the pandemic created social stigma, to the point where sick people endured social shaming for being sick and thus did not seek help. Panelists also noted the stigma falling across already-present social divides, such as along religious divisions, where certain populations were blamed for being super-spreaders.

Community

One of the biggest challenges across the board for panelists was to protect their communities and provide for people’s need for community in times of isolation, fear, and death. As a result of the widespread breakdown of social networks, people—especially vulnerable populations such as women, children, the disabled, the poor, and other socially marginalized groups—were more susceptible to domestic violence, stress, and other forms of physical and mental instability.

Solutions:

Despite facing many challenges during the pandemic as outlined above, the panelists also described the innovative ways they and other faith actors were successful at addressing the needs of their communities in these exceptionally difficult times.

Just as technology could be used to spread misinformation, it could also be used to curb such a spread. Panelists noted the ways technology helped create a bottom-up, peer-learning approach to information distribution facilitated by faith leaders that addressed widespread distrust in vaccines and other health practices promoted by the government. Similarly, faith leaders successfully used technology to adapt faith practices to digital spaces, helping counteract some of the negative effects of isolation and restrictions on religious gatherings.

“Local faith actors in Egypt led online counter narrative campaigns against hate speech and false stereotypes related to COVID-19 while ensuring empathy and unity by encouraging faith communities to help others.” – Monica Tawdros

“In the midst of restrictions, faith actors of different religions actually devised a very innovative way of interacting with their followers using phone calls, internet, email messaging, WhatsApp, and Zoom meetings. While most people do not have access to internet, faith actors used radio and television to reach their people.” – Prof. Kalinga Tudor Silva

Outside of the digital realm, panelists described their work reaching out to marginalized and stigmatized populations, including children and the sick. Preexisting faith community networks thus were well placed to address the difficulties caused by isolation and restricted movements, where other actors were less willing or less able to reach. Panelists noted as well how faith leaders were often more trusted sources of authority than secular governments or international actors, and thus could be leveraged to inhibit the spread of misinformation.

Panelists also reported how interfaith cooperation was another common solution which local faith leaders adopted to address challenges during the pandemic. Multiple panelists cited examples of how interfaith cooperation helped to counteract discriminatory policies as well as distribute resources to a greater number of people in need beyond the bounds of a single faith community.

Mental Health and Faith during the Pandemic

The panelists next discussed the role of local faith actors in addressing the mental health and psychosocial needs of their communities during the pandemic. They began by noting how restrictions on faith gatherings and the overall breakdown of physical contact within faith communities had an overwhelmingly negative effect on the mental health of many people.

The confusion and fear characterizing the first months of the pandemic were made more difficult due to the lack of mitigating support from faith communities. However, panelists noted that even when physical faith networks would break down, individuals still processed their fears, confusion, and needs within faith frameworks. Thus, panelists drew an inseparable link between mental health and faith during the pandemic.

Accordingly, many panelists described specific measures taken by local faith actors to address the mental health needs of their constituents. These included using technology to reach out to isolated individuals and adapting rituals, sermons, and chanting to digital spaces. In addition, panelists described working to supplement the needs of children in the absence of schools and the needs of the bereaved in the absence of communal ways to process the deaths of loved ones.

“When the people couldn’t go to church, the church went to the people. We visited communities in neighborhoods where we were already immersed and trusted as faith leaders. We found ways to deliver messages to the community and make sure that their stories, concerns, and confusions were heard.” – Br. Reynaldo Barnido

II. Lessons and Recommendations

As a final exercise, our panelists discussed their take-aways from the COVID-19 pandemic and their recommendations for the future. All of the panelists came away from their experiences during the pandemic with the understanding of the central role local faith actors play in their communities, and thus the necessity of involving them in future humanitarian work and decision-making.

“As faith leaders and actors, you are in a very powerful position of having trust within your community and having a platform, and being able to elevate those evidence-based and science-backed content, advice, and information around vaccination and social measures that will help reduce the spread of the virus and effectively save lives. This is a very powerful position to be in.” – Dr Bnar Talabani

Panelists cited the power of local faith leaders to impede the spread of misinformation and stigmatization, as well as guide their communities in positive physical and mental health practices. By mobilizing their communities, local faith leaders are able to raise funds and carry out relief services to people within and outside of their faith community much faster than state agencies. Faith leaders also play an important role in peacebuilding, as we saw from the interfaith responses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Beyond the centrality of faith actors, the panelists highlighted the adaptability of religion, whose innovations despite various obstacles continued to allow faith communities to persevere in changing times. Oftentimes these innovative practices came in the form of technological developments, which panelists also cite as an important lesson for the future. As we saw, in the digital age technology both facilitates the spread of misinformation leading to an “infodemic,” but also can be leveraged to mobilize and educate communities. Finally, panelists highlighted the role of women and children in mobilizing and educating at the local level.

III. Media

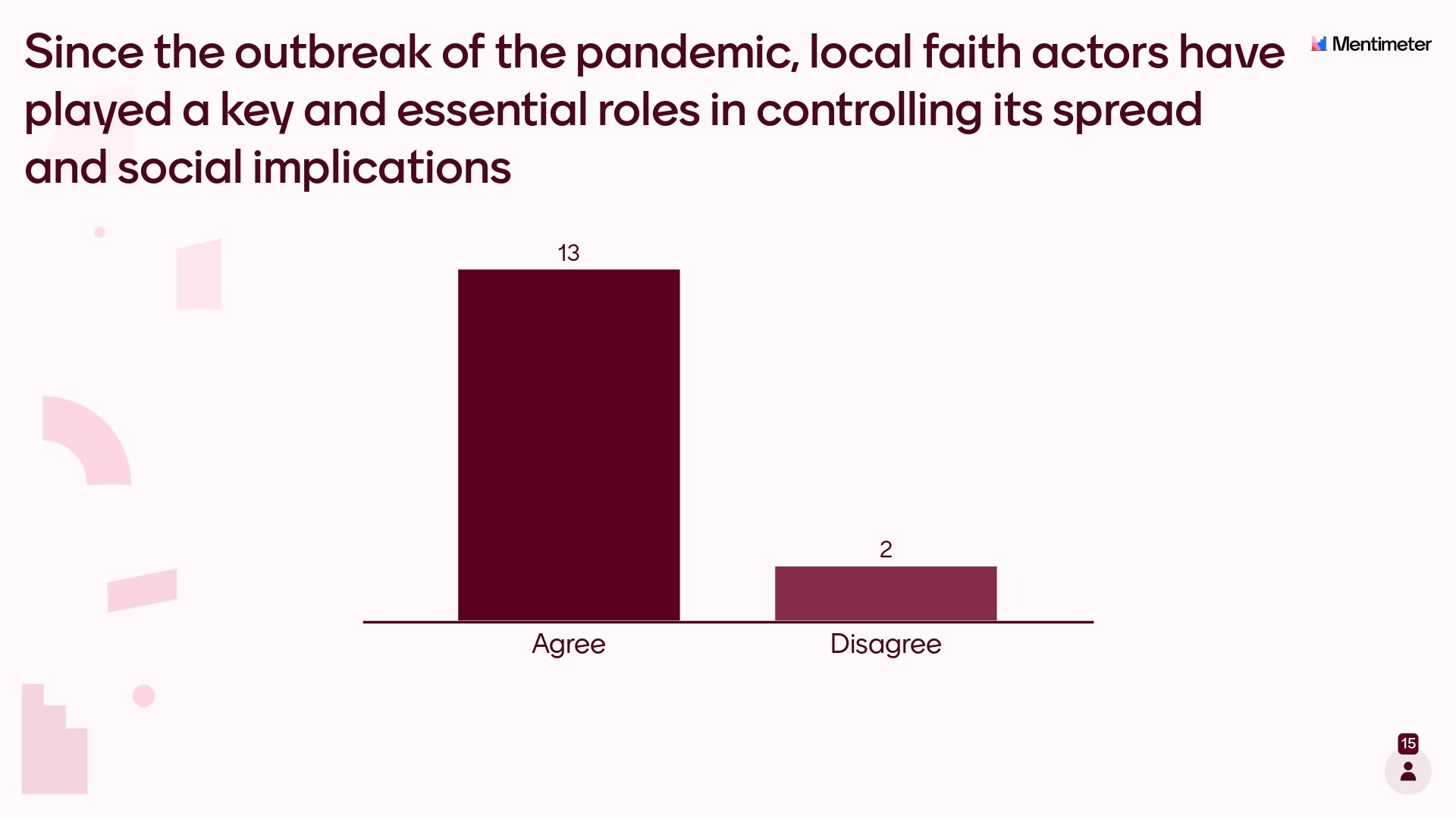

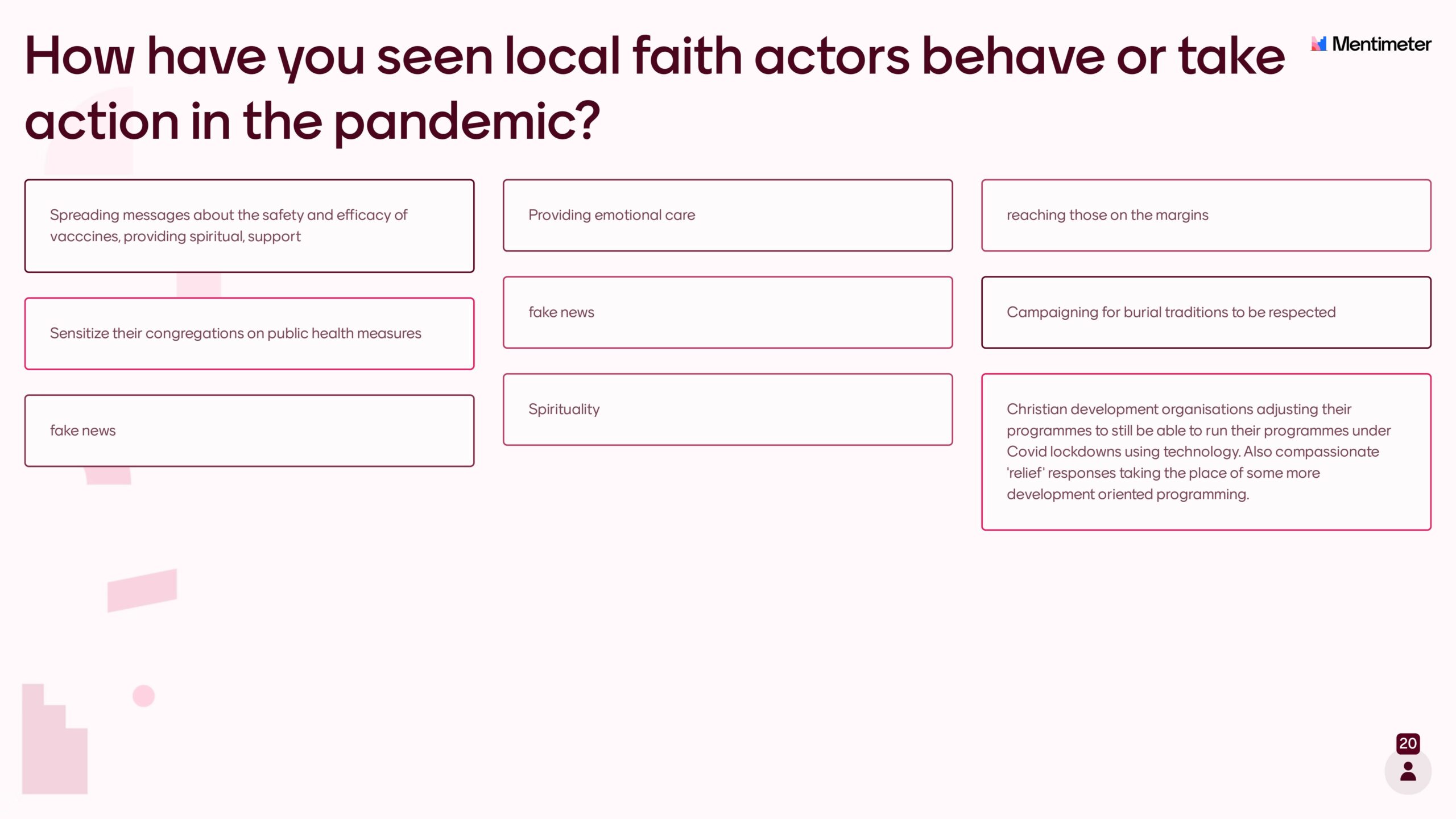

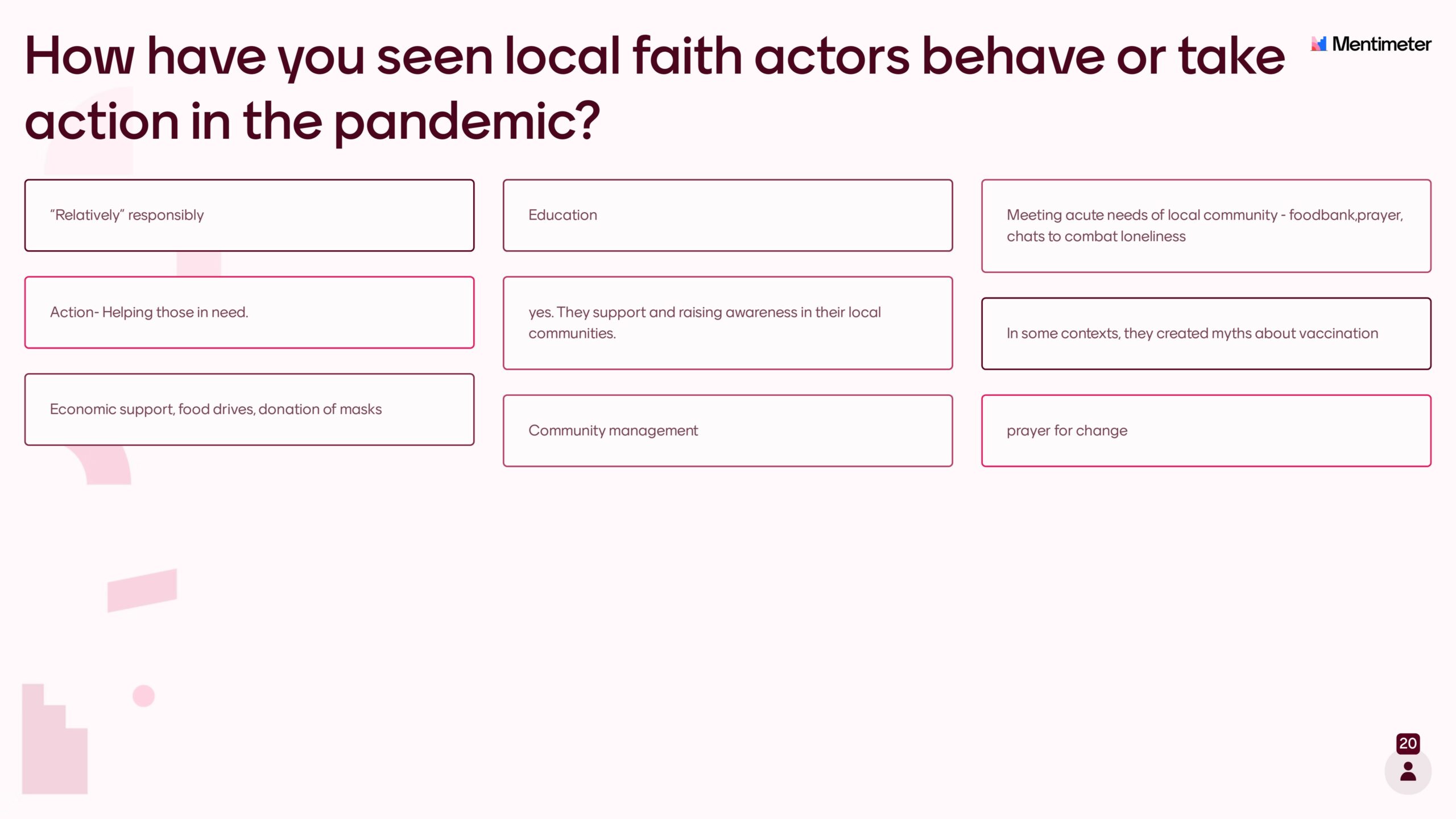

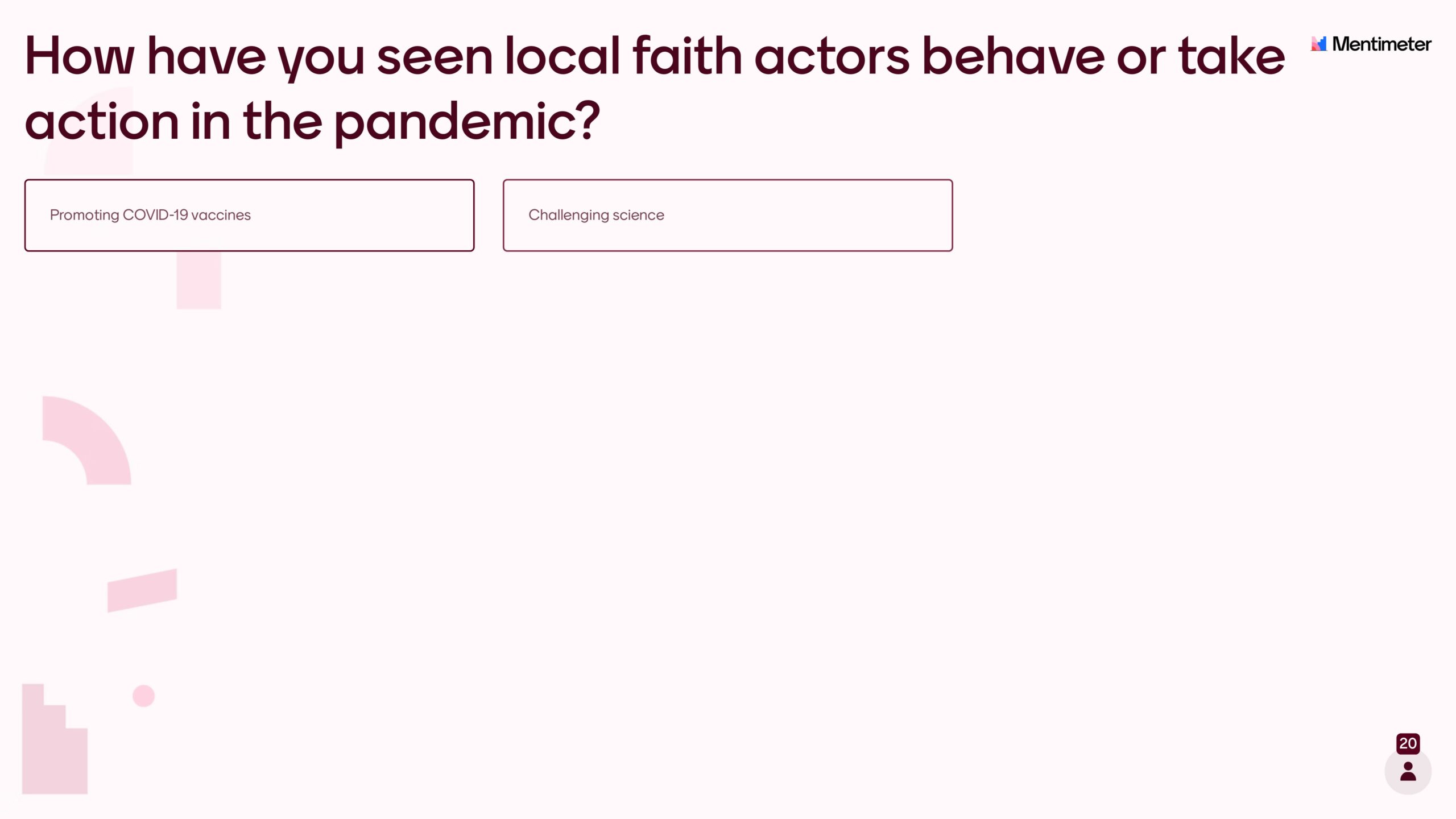

As the panelists answered questions during the webinar, so too did the audience via interactive polls.The vast majority of respondents agreed that local faith actors were central to controlling the spread of the pandemic. In response to a question asking about the ways faith actors behaved during the pandemic, most respondents mentioned positive actions such as providing support services and community mobilization. A couple, however, mentioned negative behaviors such as spreading misinformation about vaccines and other health practices.

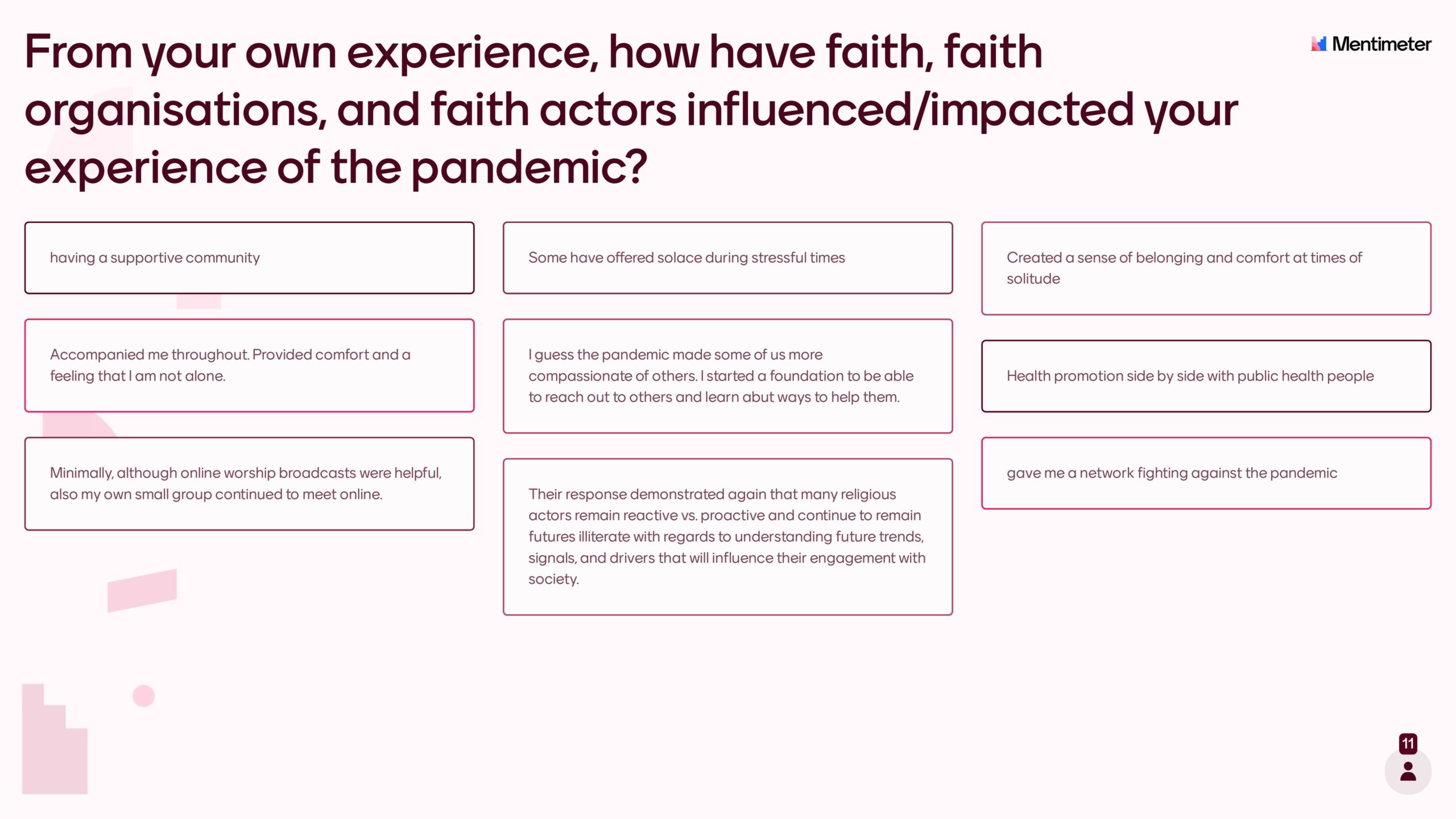

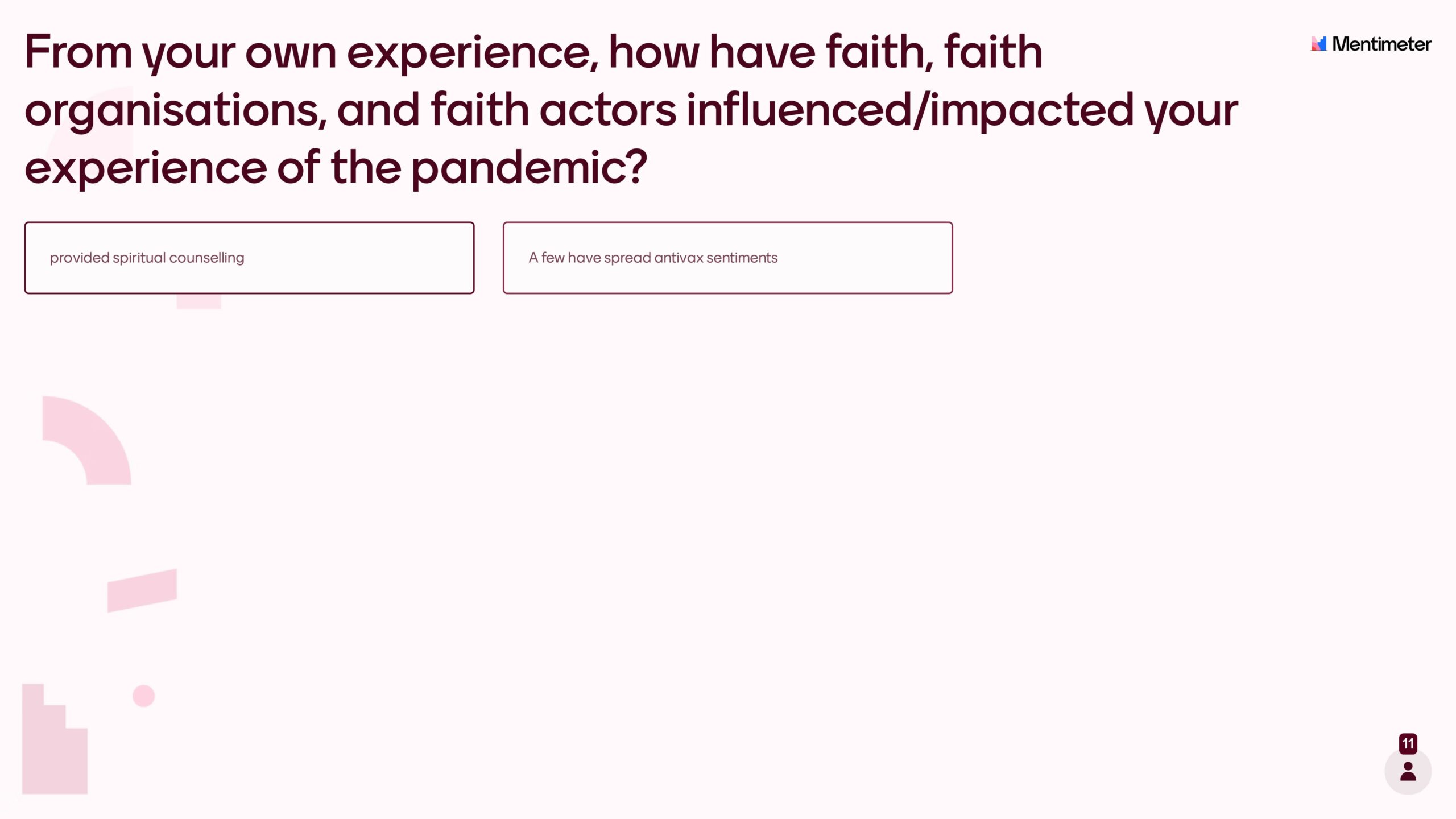

Later, respondents answered another question about the ways faith actors impacted their experience of the pandemic. The responses to this question were far more mixed, ranging from negative to neutral to positive. Some people received spiritual care from faith actors, others experienced very little interaction or impact by faith actors, and still others felt that faith actors were “reactive rather than proactive” during the pandemic.

Read more about the event and speakers here.